by Andrej Sagaidak

edited by Dele Williams

April 2, 2019

A comparative analysis of four major foreign powers’ policy strategies towards the African continent

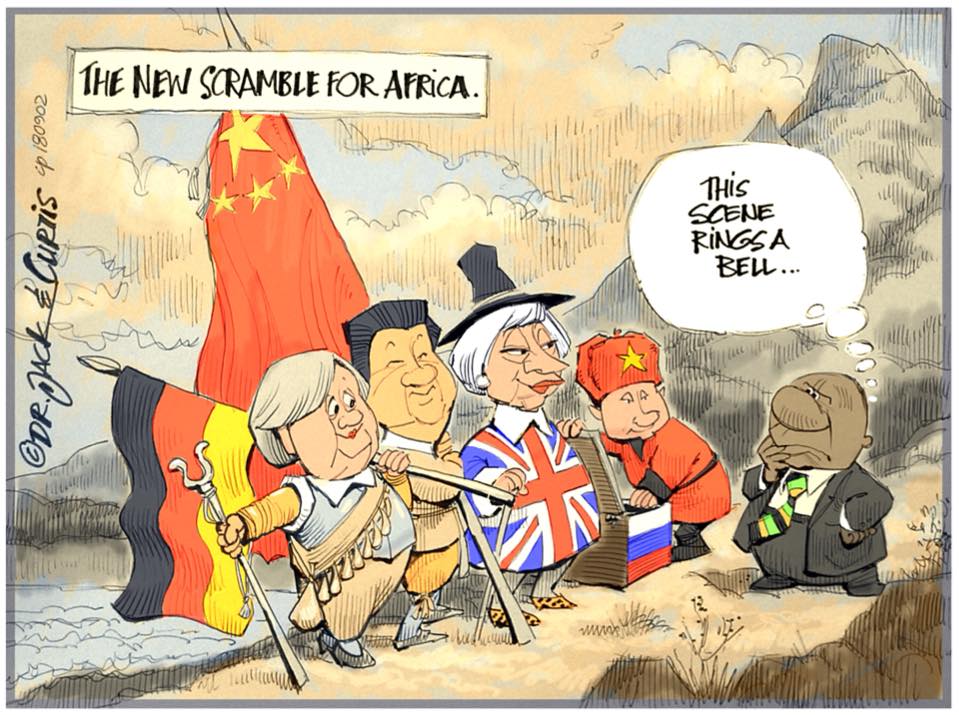

The term “Scramble for Africa” describes the European colonisation, occupation, and division of African territories during the period of New Imperialism between 1881 and 1914. Today, various countries invest exponential sums of money to secure their influence in the region. This article compares the approaches Russia, China, the EU, and the USA use to secure influence and profitability in Africa.

The evolution of the term

The evolution of the term could be divided into three parts: the original, post-independence, and post-Cold War. The original “Scramble for Africa” carved up the African continent into colonies by the leading European powers, which violently subjected its people and plunderedthe regionsof its rich natural resources. As the post-independence era commenced, African states’ colonial past made them weak pawns in the world economy and exposed them to Cold War rivalries.

The third and most recent part of the evolution that experts still relate to the post-Cold War period, could be summarised by the occurrences of the last ten years. Writer Lee Wengraf, states that in recent decades, the West has choked Africa with an “onerous debt regime, forcing many nations to pay more in interests on debts to the World Bank and International Monetary Fund […] than on health care, education, infrastructure, and other vital services combined.”

The legacy of Western domination has left Africa devastated with crippling rates of poverty, hunger, and disease. Wengraf adds that the new scramble for Africa is characterised by a scenario in which main players like the United States, European Union and People’s Republic of China (PRC)seek to “consolidate their grip on Africa’s oil, its minerals, and other resources.” Those other resources include tantalum, mainly in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which sparked the second Congolese war back in August 1998.

The methods by which various powers implement their interests vary. The increasing oil and raw material prices have produced a boom in some African countries, as well as a marked jump in foreign investment, especially by Western and Chinese capital. Western powers’ real concern is that African states will opt for Chinese deals to free themselves from the punitive conditions of IMF-World Bank loans and other forms of financial dependence on Europe and the United States. As Willian Wallis and Geoff Dyer wrote in their 2007 FT article, Wen calls for more access for Africa,“[w]ith all the revenue, they [African leaders] don’t need the IMF or the World Bank. They can play the Chinese off the Americans.” The authors also debate that “[w]ho needs the painful medicine of the IMF when China gives easy terms and builds roads and schools to boot?”

Russia following USSR’s footsteps

Recalling the events of the Cold War, the Soviet Union had one of the strongest influences in Africa. Yet, that changed with the dismemberment of the USSR in 1991 bringing territorial dissolution of 15 states. It also brought ideological discontinuation of socialism as the political incentive. While the Kremlin seemed like it entirely lost its influence in the continent, today’s Russia under Vladimir Putin is starting anew with the imposition of its foreign policies on the continent.

Russia’s role in Africa has not changed from its predecessor in terms of implementing its foreign policy mainly through military means. For example, Moscow is still engaged in regular arms supply to the Central African Republic, after it was initially allowed by the UN in December of 2017. It has also imposed itself as a mediator between the CAR government and rebel armed groups in talks in Sudan. This undermined the African Union’s own mediation. There have been claims Russia is using its ‘mediator hat’ as a cover to negotiate access to diamonds, gold, and uranium in rebel-controlled areas.

Dr. Stephen Blank stated that “[d]emonstrating Russia’s influence in Africa shows domestic audiences that Russia under President Putin is truly the great power it claims to be.” Hence, promoting its deep-rooted belief that it is a great global power, who by definition has to be present across the world.

China’s role in Africa

On the other hand, The Peoples Republic of China (PRC) remains one of the leading scramblers, as its role in the African continent is defined by the financing of more than 3,000 infrastructure projects. China has also extended more than $86 (£65) billion in commercial loans to African governments. In 2015, President Xi Jinping pledged $60 (£45) billion in commercial loans to the region, which would increase lending by at least 30 percent a year if that pledge is fulfilled.

The PRC has become the region’s largest creditor, accounting for 14 percent of sub-Saharan Africa’s total debt stock. Comparing its investments for the past twenty years, we see a surge of 40 times, now exceeding $200 (£152) billion. Today, PRC has more than 10,000 firms operating in Africa, about a third involved in manufacturing.

As China is looking to implement the Belt and Road Initiative—one of the biggest public works programmes ever undertaken—Africa stand to benefit significantly from the world’s most populous country’s investments, as it could bring to bear large tranches of grants and loans for public infrastructure works.

EU’s role in Africa

The European Union launched the Africa-EU Strategic Partnership and the first-ever summit between the 27 member states of the EU and the 54 nations of Africa in 2007. The summit proclaimed a new ground breaking point in the two continents’ partnership. Over the past 10 years, the EU has worked with a large degree of success in Africa, basing its cooperation model on reciprocal trade. The fifth EU-Africa summit that took place in Abidjan in 2017 to discuss two-way trade exceeding $300 (£228) billion, pledged to mobilise more than $54 (£41) billion of “sustainable” investments for Africa by 2020.

The EU is securing commercial positions in Africa through a web of free trade agreements and Economic Partnership Agreements (EPAs), which Brussels is negotiating or has concluded with 40 African nations. The EU approach has not been without its challenges. This is exemplified by limited progress in getting Nigeria to sign off on the EU Africa Partnership Agreement. Nigeria, the most populous, and arguably the biggest economy on the continent contends that its industrialisation strategies will be negatively impacted. It has to be said that Brexit and the general chaos surrounding the EU – UK Exit negotiations in the last two and half years means limited progress has been recorded in advancing the agreement.

Ultimately, the EU can rely on lessons learned from decades of experience with regional economic integration. For instance, it could supplement the Continental Free Trade Agreement that was signed in March 2018 by most of the African Union members in Kigali.

US’s role in Africa

The US has a slightly contrasting approach compared to the EU’s investors. Particularly, it has a non-reciprocal trade agreement called the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA). It grants about 40 African countries duty-free access for nearly 6,400 products to the US Market. The Act has had a mixed legacy, given its goal of growing Africa’s export markets rather than building two-way trade and investment partnerships. AGOA did, in fact, integrate trade and investment into Africa creating more than a million jobs, directly and indirectly. However, only a small amount of countries (South Africa, Lesotho, Kenya, Mauritius, and Ethiopia) have taken significant advantage of the opportunities offered by AGOA. And, while the EU and China invested in assertive free trade strategies, surging trade and commercial loans respectively, the US is left in search of a new commercial strategy for Africa.

The Trump administration unveiled a new strategy towards Africa – July 2018, stating that the US interests and priorities must come first in all dealings with the continent. US National Security Adviser John Bolton, outlined that trade and commercial ties must now benefit both the US and African countries, but, the US will not provide “indiscriminate aid” and will no longer fund “corrupt autocrats who used the money to fill their coffers at the expenses of their people…”

Indeed, the US commercial involvement in Africa has decreased dramatically over the last five years. Two-way trade has fallen from a high of $100 (£76) billion in 2008 to only $39 (£29) billion in 2017 due in part to US energy self-sufficiency. Whilst the US is still the largest investor in the continent—it needs to do more. There exist important building blocks that could enhance the US commercial presence in the Africa regions. Back in 2018, Witney Schneidman and Joel Wiegert wrote that the challenge for the Trump administration is to develop a coherent trade strategy for Africa that builds on AGOA, basing its arrangements on reciprocity and utilising existing programmes to enhance the US commercial presence on the continent.

The Scramble in retrospective

Overall, the world recognises that Africa still has huge potentials and the dynamics of the modern “Scramble for Africa” reveals how different actors go about securing their interests on the continent. While China invests in infrastructure, the EU approaches its deals based on reciprocal trade, and the US which hitherto granted non-reciprocal duty-free access to its market, is now leaning towards reciprocity, Russia’s engagement is defined by strong military presence. Carnegie Endowment senior fellow Paul Strowski affirmed in Russia’s case that “[w]hen it started its return in the last couple of years, the Russian position in Africa was in a sorry state, particularly in comparison with China. It can’t offer consumer goods like China but, what it can offer is arms and occasional debt relief, either in exchange for arms deal or the rights to explore and drill for hydrocarbons or other extractable.” Strowski concluded that “[w]hat we are seeing is a Russian return that is trying to find a niche where they can be competitive. The niche they really own is arms.”

In conclusion, the fact that the US is rapidly losing influence in the continent both bilaterally and multilaterally, gives expansion opportunities to other actors. It offers other partners, such as the EU and China space to shape developments on the continent in a way that support their own agendas, as well as, promote the priorities of African countries. The United States will continue losing position if it does not act swiftly to adjust its short sighted approach within a rapidly progressing continent.

andrej@africanstudies.org.uk

National Institute for African Studies (NIAS)

dele@africanstudies.org.uk